Have you ever thought about how you could access your healthcare records, if you ever needed to? Where to find the history of every appointment, every immunization, every emergency room visit you’ve ever had?

Fourteen weeks ago, we were assigned to partner with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to think of ways to improve healthcare records access, as a five-person student team in a field class at Harvard Kennedy School.

This was the first time some of us ever thought about accessing our own healthcare records—or even contemplated the idea that access to health records could be a challenging process. For us, as healthy, young students, we never really needed access our own health records. And when we started a talking to people on the street as part of our research process, asking them to think about accessing their healthcare records, we quickly realized that for many people, access to their health care records is not top of mind!

As we dug deeper, however, we discovered a very different reality for some people who needed access to their healthcare records urgently in the past but ran into challenges. Examples include:

A patient who fell ill and wanted to see his past medical history to explore treatment options;

A patient who recently changed doctors and needed to fill out a list of medical history records but couldn’t remember enough details; and

A caregiver who needed to pass her mother’s healthcare records onto to a new provider.

Some of these people were like us—people who never thought there would be one day they would need their healthcare records, nor that it would be so difficult to get access to them. People who also had no idea where to start looking for all the records, what rights they had to access the records they needed, and who to turn to for advice.

Over the course of the semester, our student team realized that helping this group of people when they most need it can potentially have a huge impact. It may not be that everyone will require their healthcare data all the time, but everyone will probably require their data at some point in time in their lives. We want to increase the possibility that these people will get the healthcare data they need with as little hassle as possible. At the same time, we identified a lack of easy access to consumable information about specific healthcare data access rights for both patients and providers as the primary issue we would focus on.

Why is access to healthcare data difficult?

This isn’t a universal issue. Many doctors and health care systems are actually doing a good job in providing patients easy access to healthcare data. However, in cases where patients cannot get the healthcare data they need, the crux of the issue is often about the balance of access and privacy. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is the law that governs how healthcare providers must protect patient healthcare data and also responsibly share it. To us, it was somewhat counterintuitive that same law emphasizes privacy while also emphasizing portability.

Because of how complicated HIPAA is, providers and patients often do not fully understand their responsibilities and rights with healthcare data. Too often, providers focus on securing healthcare data, ensuring patients’ privacy is protected—but often at the cost of allowing patients easier access. On the other hand, patients are not likely to know their rights to access their own healthcare data—and often don’t care until they immediately need access.

Ideas to Help Patients Access Their Data

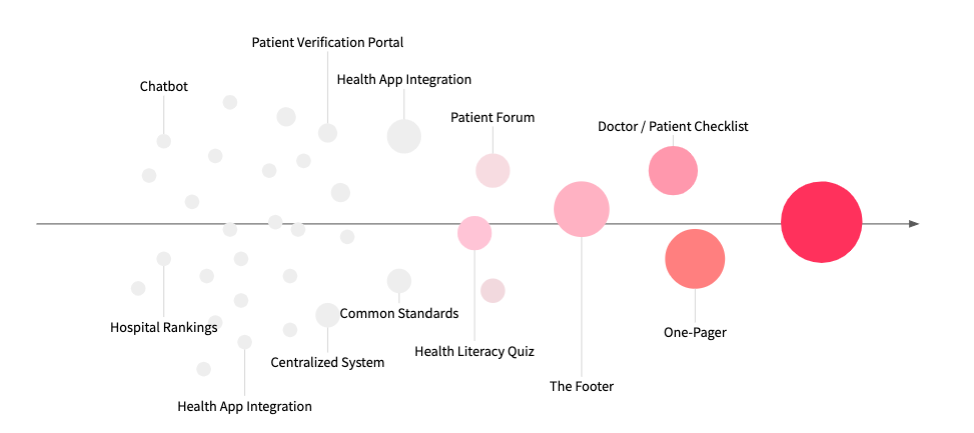

After researching the issue with residents of the Boston area, prototyping ideas, and testing our solutions with additional residents, we came up with a few resources primarily aimed at helping patients access their data better:

1. Troubleshooting Guide for Patients

We propose to create a service to help people move past the hurdles they may face when they trying to access and retrieve their records. Through an easy-to-use website with a simple questionnaire, we provided personalized resources to help people access their records more easily, ranging from curated “tips” to an email template that patients can use to send to their doctors. The guide is targeted to both inform and empower patients to have reasonably easy access their health information whenever and however they wished to.

Video of Carrie, a Medicare beneficary, trying our troubleshooting guide:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1c-PdlgXwjocMj0pFal3vBP30qCPq7fMZ/view?usp=sharing

2. Implementing SEO for HHS

Google “how do I access my medical records.” There are many sites claiming to provide answers, but we believe that people should get their information directly from HHS if possible. We would recommend that HHS implement a search engine optimization (SEO) strategy—i.e. make it easier for people searching for information about health records access to find the relevant HHS webpages, focusing on the keywords and questions that people actually use.

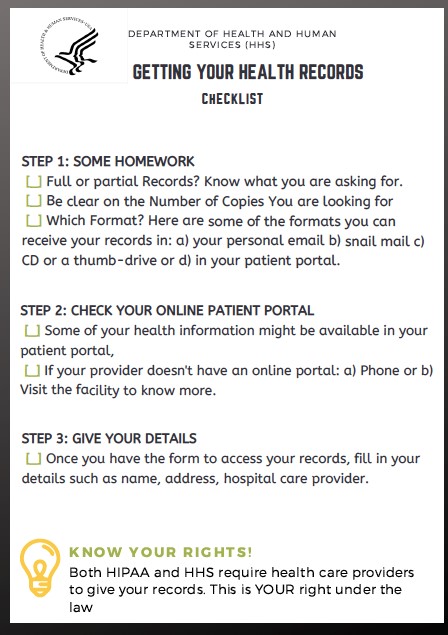

3. Creating a How-to Checklist

We didn’t know the steps to take to access our healthcare records before this project, and most people don’t either. Clearly defining the steps in a simple checklist could eliminate uncertainty from this process.

Conclusion

We’re now excited about health data! We’re excited for the future where we can collectively feel empowered by our healthcare data. In our day-to-day lives, wouldn’t it be great if we could use our healthcare data and medical history to make better choices for ourselves?

One key insight we had this semester was that health operates on a spectrum. It makes sense once you think about it: we all spend our entire lives moving between healthy and unhealthy. When we are unhealthy, we want to do everything we can to get better. Yet without access to our own health care data, it can make it harder to participate meaningfully in our own care decisions—leaving you feeling helpless and frustrated. There is knowledge and power to understanding your own records and finding the doctor that can best help you.

Think of it this way: Our health records already exist, so why don’t we make some use of them?