This post is the last in a series produced for a Harvard Kennedy School field class on innovation in government. Our team has been working with the U.S. Census Bureau. You can learn about our journey through our blog and our final presentation. You can find our prototype for a re-imagined income inequality topic page here.

In roughly three years, the U.S. Census Bureau will begin collecting data for the next decennial survey—Census 2020. The Bureau’s operational plan has already been released and collection testing is underway. The question we’ve been thinking about as we conclude our project with the U.S. Census Bureau is:

When a user visits census.gov, what will they see?

What experience will they have?

We’ve kept this question in our mind as we created our five policy recommendations for the U.S. Census Bureau. Along with our prototype and user research, these recommendations are our final deliverables to our client.

The above shows our five policy recommendations, informed by user research and conversations with our colleagues at the Census Bureau

First, the 2020 census user should land on a website with a simplified look and feel. Users find the current website overwhelming and difficult to navigate. When we visited Census HQ, we saw a number of technology modernization projects currently underway to address this. These projects align with many of the insights we uncovered in our research, and could be even more effective if focus is placed on testing with real users early and often.

While the Census is hard at work reinventing content management and customer service, there isn’t a project to redesign the census.gov homepage and simplify the site structure. To fill this gap, the Census Bureau should initiate a project to redesign Census.gov.

Census should initiate a project to redesign the Census.gov homepage (current homepage pictured above)

Second, the 2020 census user should see how the Census Bureau fits within the ecosystem of government and non-government data partners. We found that users rarely start and end their data searches at Census.gov. They often visit other data sources and consume data-based research and media related to their search.

To cater to this user need, the U.S. Census Bureau should partner with innovative data organizations—both inside and outside government—and feature the work of others alongside their own. By engaging with other agencies and data experts, Census can offer its expertise to the data community and invite suggestions for improved content. For example, Census.gov could feature valuable data visualizations, like Data USA, to show how organizations are making new use of Census Bureau data.

Data USA is an example of an innovative website, built outside government using Census Bureau data. The Census Bureau should partner with organizations like Data USA.

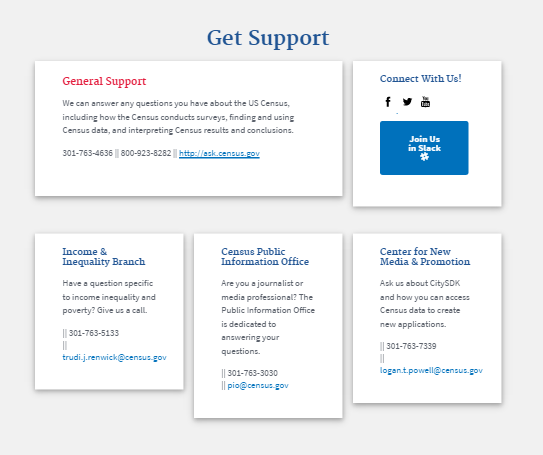

Third, the 2020 census user should clearly understand how to get support. Currently, the U.S. Census Bureau invests significant resources in support. When users do access support, we found their experience was overwhelmingly positive. However, users sometimes struggled to understand which support channel was most appropriate for their request, and this sometimes deterred them from contacting the U.S. Census Bureau.

A first step would be for U.S. Census Bureau to clarify the specific mandate of different support bodies—e.g. clarifying the differences between Census Regional Offices vs. Census Information Centers vs. State Data Centers vs. Data Dissemination Specialists. The U.S. Census Bureau can then communicate clearly to users where to go to find the support they need.

Our prototype provided a more intuitive support section, designed to quickly direct users’ queries to the appropriate Census Bureau channel.

To achieve these recommendations, the U.S. Census Bureau should continue to add talent with skills in user experience and front-end design. The U.S. Census Bureau has already begun to do this, especially in the Center for New Media and Promotions (CNMP) team. The U.S. Census Bureau should continue this effort and also create an internal community for staff not part of the CNMP team but who are interested in user experience and design.

Signing off: this is our final blog post! Our final presentation, covering all our work across user research, prototyping and recommendations is available here. We would like to thank our colleagues and friends from the U.S. Census Bureau for their patience, passion and support. We have learned a great deal and look forward to continuing to contribute to the U.S. Census Bureau’s important mission in the future.

Luciano Arango, Nidhi Badaya, Aaron Capizzi, Rebecca Scharfstein, Peter Willis