Why is municipal voter turnout so low in the City of Boston? And what should the City do about it?

We set out to explore these questions as a team of Harvard students in the field class Tech in Innovation in Government. We’ve blogged about our journey so far:

Part 1: We spoke with Boston residents to understand their reasons for voting or not voting.

Part 2: We interviewed voters on Super Tuesday and analyzed Boston’s voter turnout data.

Part 3: We prototyped solutions for increasing voter turnout.

Pre-COVID-19

Based on our field research, we brainstormed a wide range of ideas to increase voter turnout. Some of our favorite ideas were:

SMS voter nudges: Targeted text messages to spur voter action and raise awareness of the election in the coming weeks.

Community outreach: Existing community centers and student groups could be used to distribute fliers.

Promotions: We envisioned making it easier for voters to get to the polls through promotions like waiving public transportation fares on Election Day.

Legislative changes: Other municipalities have created Election Day holidays to increase turnout. We proposed exploring these longer-term ideas, too.

The COVID-19 Pivot

In March, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and physical restrictions quickly changed our project. Harvard University closed and classes moved online. Many of our initial ideas to improve municipal voting—which relied on in-person interactions—were no longer practical.

One idea that became more compelling was reaching voters at home through the mail. This idea was gaining traction across the country. As demonstrated by the Wisconsin presidential primary, many jurisdictions began moving to vote-by-mail due to COVID-19 restrictions. We started to focus on reducing friction in the voting process through mailed communications to voters.

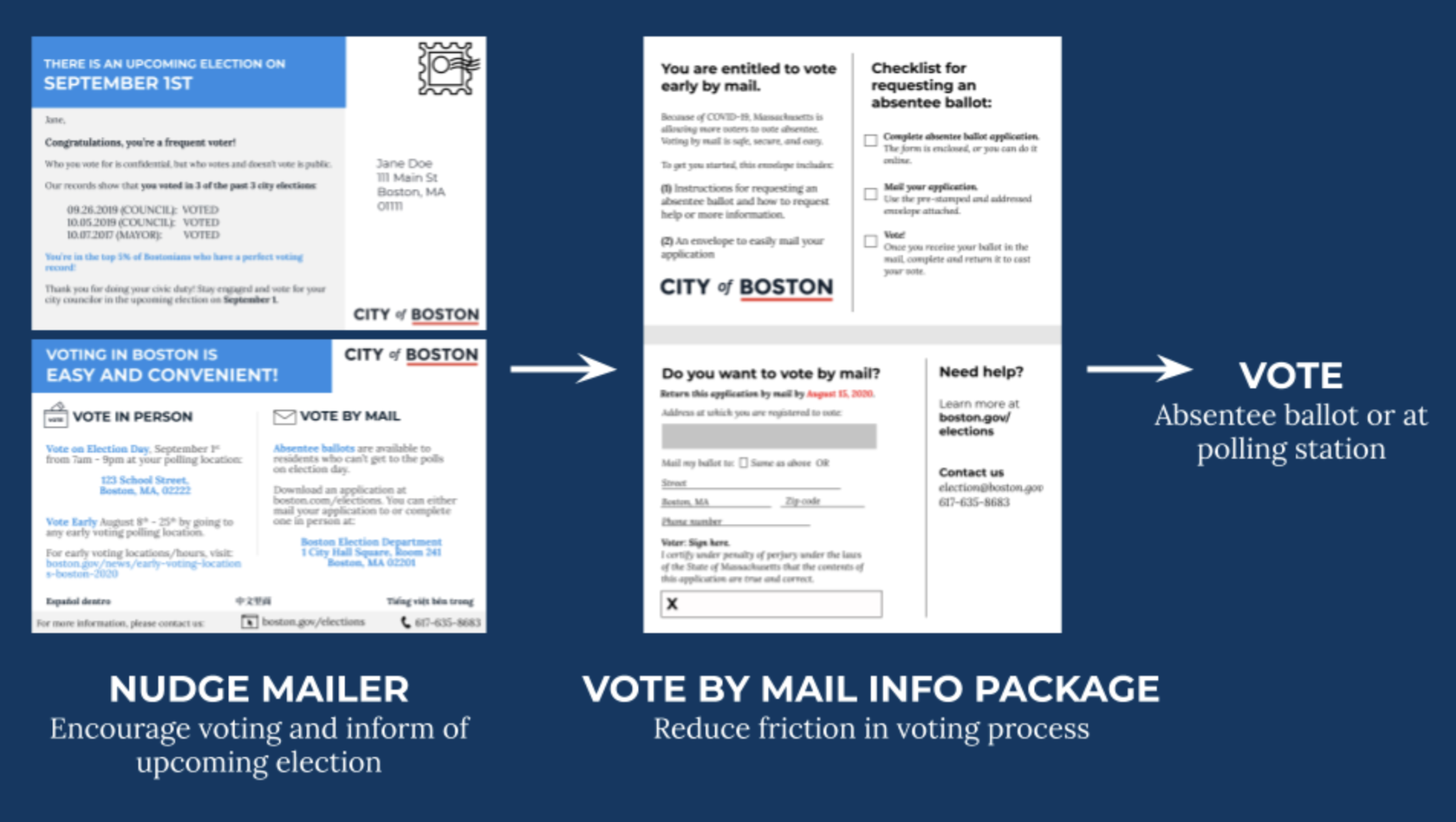

We decided to focus on two mail-based interventions: a behavioral “nudge” mailer and a vote-by-mail information package.

The New Plan

Nudge Mailer

We conceived this mailer based on the behavioral economics concept of “nudges,” which are frequently used to incentivize positive behavior. Notable examples of successful nudges include utility companies encouraging reduced energy usage and political campaigns increasing voter turnout. This New York Times article is a particularly helpful synthesis of existing research around using nudges for voting behavior.

Our research suggested that messages that focus on accountability, social comparison, and calls-to-action could make a nudge effective. We implemented all of these techniques in our nudge mailer.

Our nudge mailer is designed to:

Inform residents about the upcoming election;

Show the recipient that the City is aware of their voting behavior;

Tell them how their voting behavior compares to others in Boston;

Ask them to vote; and

Show a clear process for voting.

We designed the nudge mailer to be a fold-out postcard—the size of a standard letter-sized sheet of paper folded in half. The mailer includes the nudge printed on the front, instructions for how to vote on the back, and translations in Spanish, Chinese, and Vietnamese inside.

Vote-by-Mail Package

Our work on the vote-by-mail package was informed by both ongoing civil discourse and existing research on vote-by-mail systems.

Today, COVID-19 physical restrictions have sparked discussion about alternatives to in-person voting for fall municipal, state, and federal elections. Many states are exploring legislation that expands funding for vote-by-mail. Massachusetts customarily allows only certain voters to vote absentee, but it is temporarily relaxing those restrictions for spring and summer elections. Our vote-by-mail prototype was designed in the context of this ongoing debate and is meant to support the City’s work in ensuring fall elections are carried out safely.

To design the vote-by-mail prototypes, we leveraged research from the Center for Civic Design, a nonprofit that explores the application of user-centered design in electoral systems. The group has produced a toolkit of resources for developing and scaling vote-by-mail systems, including effectively communicating changes to voters and designing USPS-friendly materials. We also referenced research and resources from the National Vote at Home Institute.

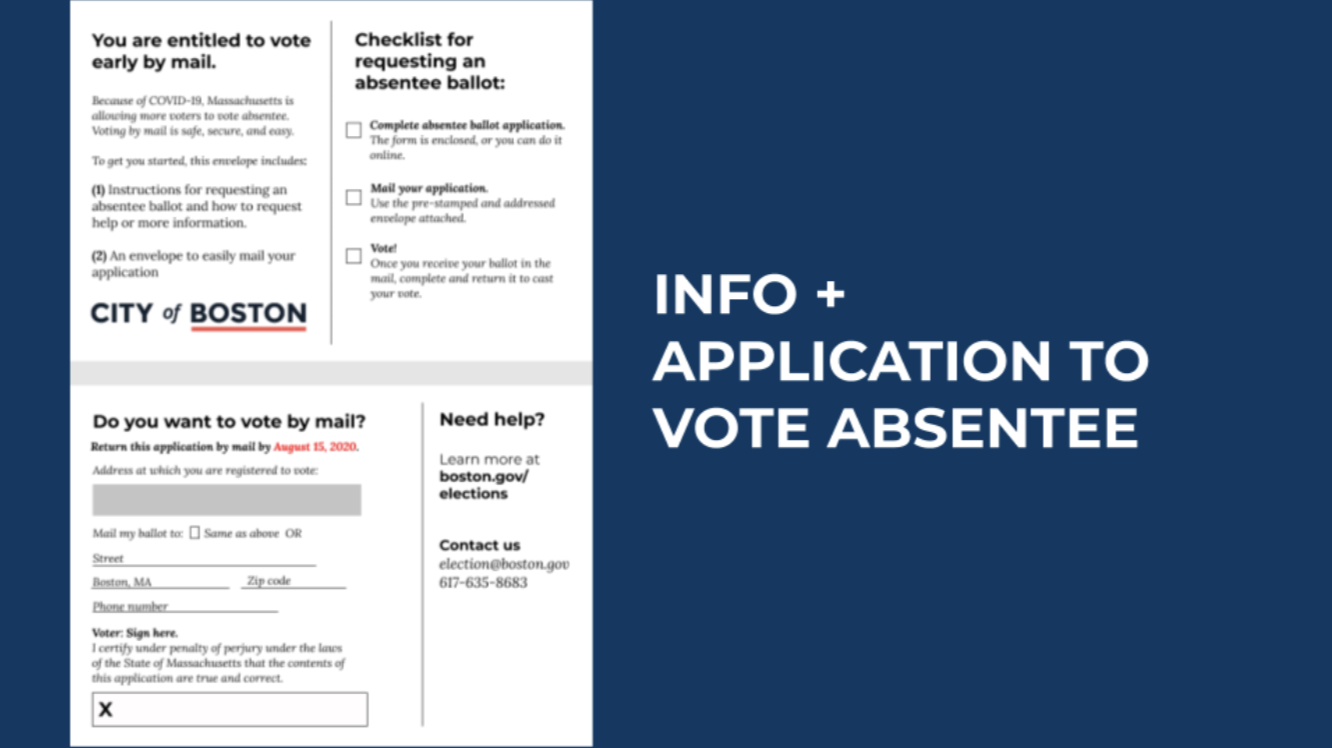

Our envisioned mailer communicates changes in vote-by-mail policies due to COVID-19 and enables registered voters to easily apply to vote absentee. The package includes an eye-catching multilingual envelope, an information card which includes an application to vote by mail and information about the process, and a pre-stamped and addressed return envelope. All materials are multilingual, with translations in Chinese, Vietnamese, and Spanish.

Our vote-by-mail package does rely on several assumptions about the fall municipal elections. First, it assumes that elections proceed on schedule. It also assumes that absentee requirements are relaxed, but that mail-in ballots continue to require an application. The mailer can be adapted if any of these conditions change. For instance, the application segment can be removed if the application requirement is waived. Moreover, if there are expanded in-person voting options, such as extended hours or drive-through voting, this information could be included in the mailer.

Testing Our Concepts

To further refine these ideas, we tested our designs with Boston residents. Here’s an early detailed version that we put in front of prospective voters:

With social distancing, we weren’t able to get voter feedback in person, so we needed to get creative in finding and reviewing designs with people.

One of our team members, Joanna Bell, had a great idea to find a group of residents on the neighborhood connection site NextDoor and gather feedback this way.

Other group members reached out to their personal networks for feedback. We also used the testing platform UserTesting, an application where volunteers (who are paid to give quality feedback) walked through our prototype mailers and gave feedback in real-time. In all, we spoke with 20 Boston residents and gathered their insights about our mailers.

We tested design elements, language, and overall reactions to the mailers (e.g., would they really inspire behavioral change?). We sought to find people across a wide range of demographics, including residents who both regularly vote and regularly do not vote.

Nudge Mailer Feedback

Some voters were very honest with us! Both positive and negative feedback helped us understand how to connect with our users and the best way to communicate with them.

The red ink on an early version was polarizing to some. One resident told us, "it makes me think people are making fun of me, or criticizing me" and it was "demotivating".

Another suggestion was to ensure the nudges were more positive and say "become one of the outstanding citizens by voting." Another suggestion was that the mailer should say "your vote helps your community recover from COVID or something to that effect.”

A final suggestion was to change the wording to, “determine how your municipal money is spent by voting” and “be a part of government oversight by voting.”

Some of our early versions of the nudge postcard had details about past voting behavior and printed them out to motivate voters to do better. Some people felt this was “creepy” and “Big Brother-ish.”

There was a real debate within the team on how to best address the tension between accountability and creepiness: some discomfort might be tolerable if it helped to motivate the voters, but we ran the risk of going too far. Ultimately, we chose a softer tone that still showed past voting participation, but in a more friendly manner.

Voter Information Mailer Feedback

Users gave us feedback on how to improve our design elements, including, “a little color wouldn't hurt anyone… Maybe a bold colored stripe or something simple enough yet eye-catching” and “the application deadline should be bigger.”

Incorporating all the feedback and using the City’s design guide, we improved the prototype and tested the final version of our vote-by-mail package with a new set of residents. We received very positive feedback on the design, the clarity of the message, and the ease of navigation.

The majority of our people who tested this version said it was “concise and easy to follow”, “it has all the information you need and is not overwhelming unlike other government mailers,” and many also felt that it was quite “official-looking,” so they didn’t doubt that it was sent by a government source.

Final Versions

After several rounds of testing, we incorporated feedback into our final versions:

Language accessibility was an important consideration. To make sure the information is available to a wide range of voters, we added translations in Spanish, Chinese, and Vietnamese

Timing Counts

We recognized these mailers need to fit into the volume of communications residents receive from the City of Boston. We needed to find a time window that was close enough to the election to remind and nudge the voters into action, but be mindful of other communications and avoid our mailers being “lost in the pile” of mail from the city. Below is our proposed timeline for our mailers.

Thank You

We’re so appreciative of the City of Boston for their patience and flexibility during this most unusual semester project. They stayed with us as we adjusted our approach and gave us consistently useful feedback to make our final products and ideas better.

The semester is finished, but none of us will ever look at a municipal election the same again. We’ll always be comparing each one to Boston’s and analyzing how effective their outreach is!

Special thanks to Dana Chisnell for her generous review of our work and her thoughtful ideas. Finally, a big thank you to Nick Sinai and the teaching team for their unwavering optimism during this semester. We couldn’t have made it without your leadership and willingness to march onwards.

Joanna Bell, Dasha Metropolitansky, Sunaina Pumadarthy, Paul Rosenboom, Molly Welch